A BIG BELL, A GREAT MAN

WRITTEN by Hayley Flynn

READING TIME: 4 minutes

The bell inside Manchester Town Hall's clock tower

Autumn in Manchester is one of my favourite times of the year for one reason only and that is the calendar of events. The Science Festival, Literature Festival, Food and Drink Festival, Comedy Festival, the Manchester Weekender and preceeding all of those, there’s the nationwide, National Heritage Open Days. And it’s that particular event which leads me the Town Hall.

There are 14 million bricks in the Town Hall and delicate images of cotton flowers and bees are set into the mosaic floors to signify the origins of our wealth and the industrious nature of our people. In the Great Hall there’s the famous Ford Madox Brown’s Manchester mural complete with a depiction of a tee-total Bridgewater glugging wine and the dark, gothic courtyard has been the set of many a London street, most recently in Sherlock Holmes and The Crimson Petal and the White. But of all the wonders of the building there is one we don’t even see from street level.

Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, although his original proposal was heavily altered from a dowdy little structure to the much grander one we see today, the town hall and its tower are a wonderfully clever use of the triangular space given to work with. Not content, however, that they were celebrating Manchester’s city status quite as dramatically as they could; six years into the project Waterhouse called for suspension of the building works and added an additional 16ft to the tower. So today the clock tower stands 288 feet high and from 1877 - 1962 it was the tallest structure in Manchester.

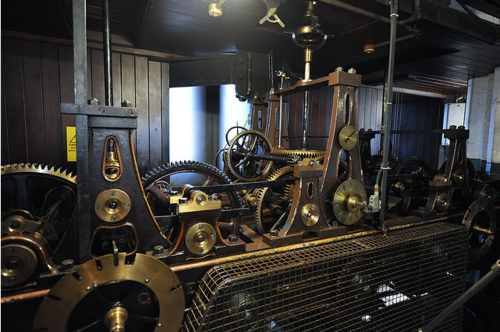

Taking the lift six floors up as far as we can there’s still a long climb up a dark, stone spiral staircase to reach the tower. One room off from this stairway houses the original mechanics of the clock itself which were amongst the largest available at the time and were custom made especially for the clock. In the bell ringing room above this floor is the original pendulum for the clockworks encased in a glass cabinet along with bright red and blue ropes hanging from the ceiling that are pulled to chime the carillon of 23 bells. These bells, manufactured by John Taylor bellfounders, are suspended above a series of trapdoors that enable each of them to be lowered to the ground floor entrance of the town hall at any point should it be necessary.

Eventually, many steps into the spiralling chamber later, you arrive at a room directly behind the faces of the clock. Inscribed above the face on three of the fours sides, and just about visible from the street, is the biblical quote 'Teach us to number our Days'.

The clock is by Gillett and Bland and originally lit behind by gas lamps. It’s 15ft in diameter with the hour hands measuring 6ft and the minute hands 9ft. The clock itself was originally powered by Manchester Hydraulic Power which also powered the lifts at John Ryland’s Library, the organ at Manchester Catherdral and rose the curtain at the Opera House.

At this point you can access the lower balcony and walk around each face. The carvings of angels have been decayed by the weather and their stumpy hands that reach out have begun to look a little gnawed at. Up here it’s also a resting point for Manchester’s famous city-dwelling peregrines, as the pigeon skeletons cast between corner turrets indicate.

From this balcony is access to the chamber which holds the bell. Great Abel is named after Abel Heywood, the mayor at the time. Heywood was a fascinating man who pioneered for inexpensive newspapers at his own cost and subjected to brief imprisonment as a consequence. He set up a successful penny reading room followed by his own bookstore, he became a radical and campaigned for the lower classes to have their say, he then became one of the commissioners of police, was prostecuted for blasphemy, became mayor of Manchester, saw the town hall to completion and finally set about dedicating his time to producing penny guides to local tourist destinations now accessible by train so that the poor could see the best of the local countryside. Abel Heywood was a man I would have liked.

It’s a shame then that his bell isn’t visible from the street and it does seem rather a large piece to keep tucked away. After repairs were carried out to reinforce the original bell it now weighs a massive 8 tons. The bell continues to count the hours and is heard across the city although it no longer swings and the clapper inside it isn’t used.

The bell itself rang for the first time on New Year’s Day 1879 and is inscribed with the initials ‘AH’ and the Alfred Tennyson line 'Ring out the false, ring in the true' which seems exactly the kind of phrase Heywood would have chosen himself and my favourite secret that the rooftops of the town hall hold.

You can view a short video about the Town Hall that The Guardian recently aired here