AND A NORTHERN QUARTER AIR RAID SHELTER

WRITTEN BY Hayley Flynn

READING TIME: 4 minutes

A peek inside a church safe and a hidden air raid shelter

At the heart of St Ann’s Square stands the only surviving 18th century church in the city (celebrating 300 years in 2012) and the second oldest in Manchester, the tower of which is said to mark the geographical centre of the old city and the surveyor’s benchmark can be seen carved into the stone by the tower door.

The church was built in 1712 as part of a redevelopment of the area and is said to be designed by Christopher Wren, or one of his pupils, and was later restored by Alfred Waterhouse. At the time of erection the tower, though not seemingly large today, was visible all across Manchester - at which time was a small market town.

One of the windows of the church is dedicated to the memory of Hilda Collens who founded the Northern School of Music (part of today’s Royal Northern College of Music).

Thomas De Quincey, born just around the corner on Cross Street, was baptised at the church and you can see the gravestones of his immediate family right outside. De Quincy wrote what is thought to be the very first book about drug addiction; Confessions of an English Opium Eater, and indeed he had quite the addictive personality - taking his opium dissolved in alcohol and stating:

“I am bound to confess that I have indulged in it to an excess, not yet recorded of any other man”.

Addiction literature was born.

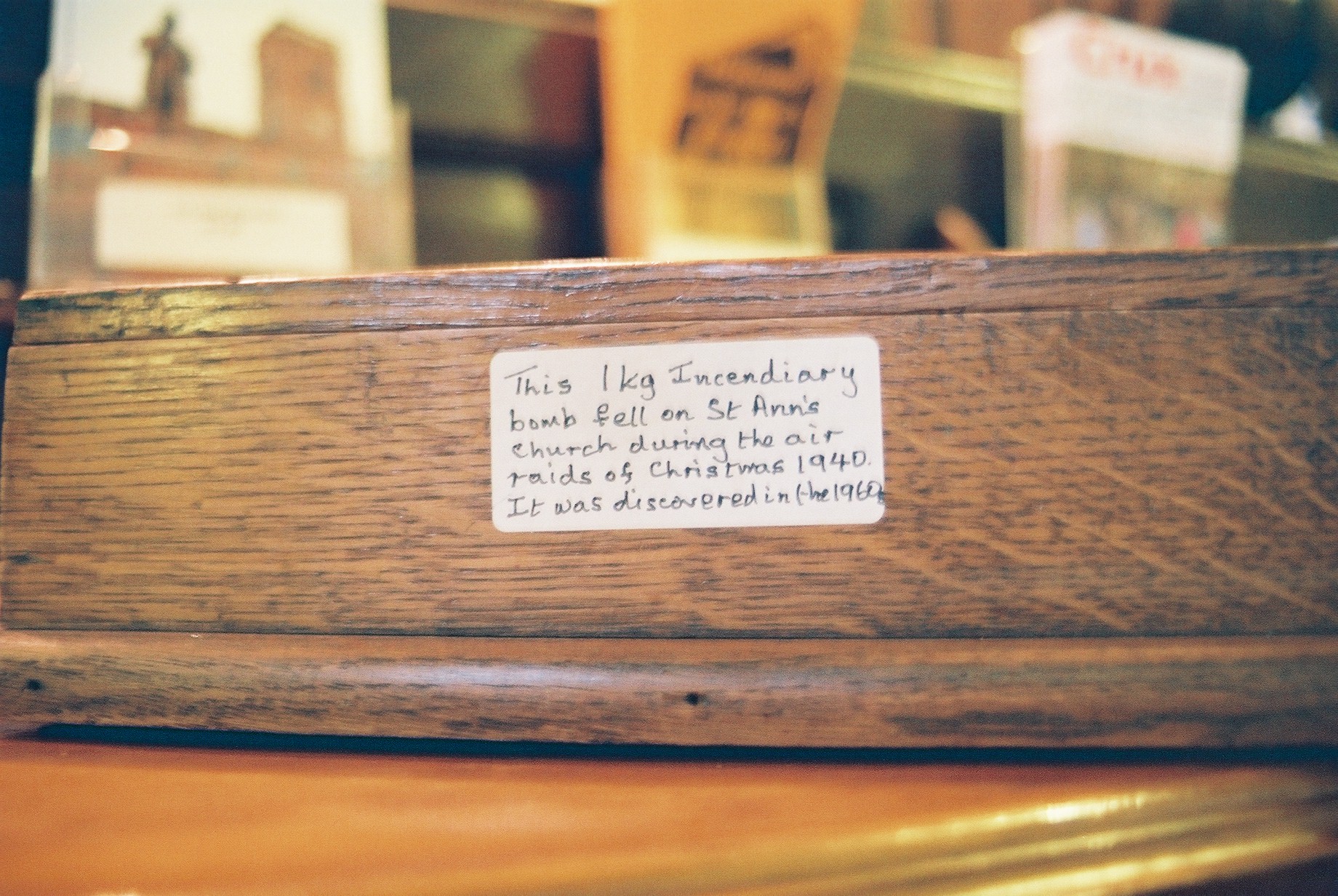

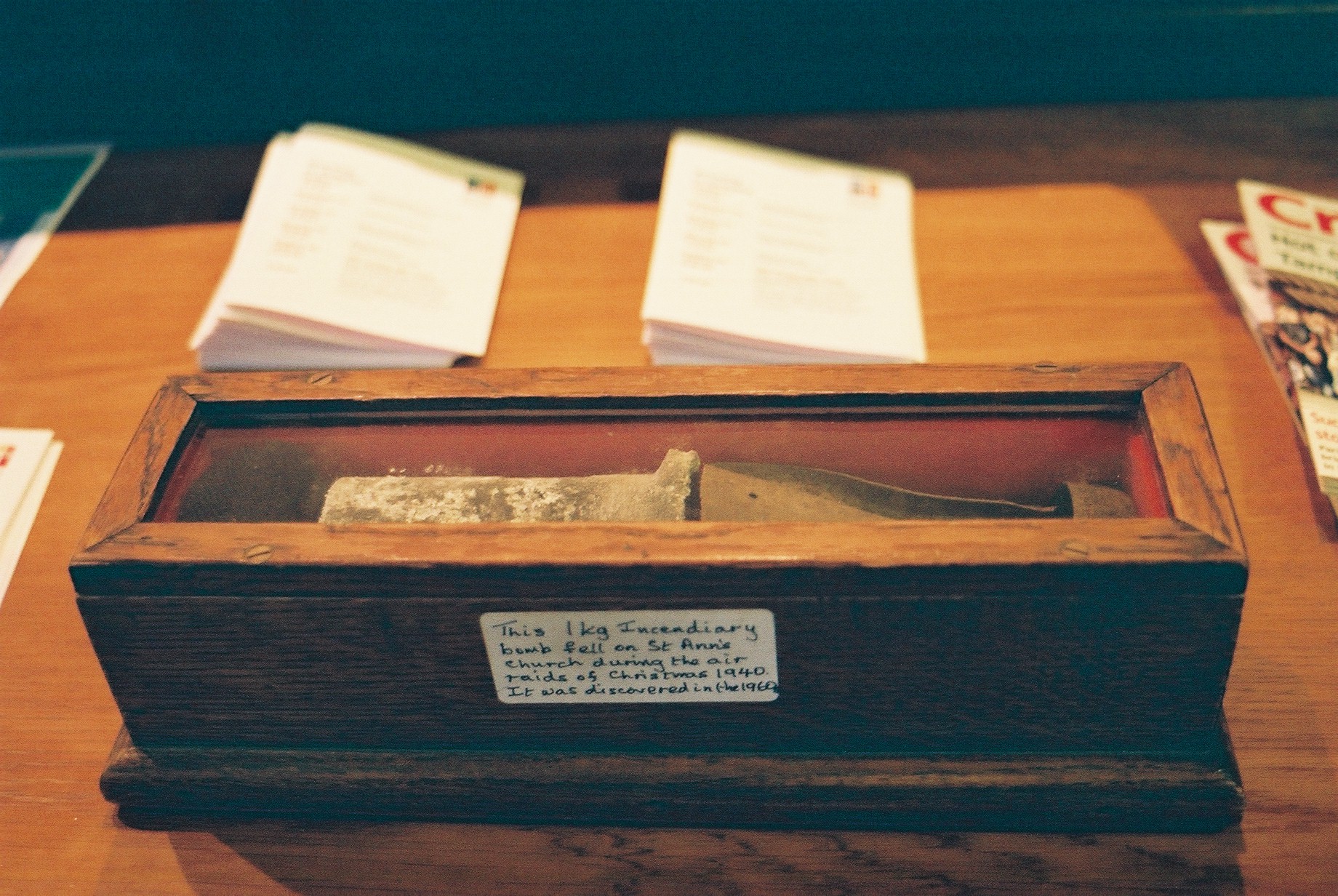

During the air raids of the Second World War churches would often fall victim to the blasts, yet St Ann’s seemed to be lucky enough not to be targeted. Or at least that seemed to be the case until 1960, because St Ann’s has a secret and that secret is hiding in its safe. A bomb.

In 1960, during repair works to the church, an unexploded bomb was found on the roof and since then the bomb has been locked away in a safe in the church.

Surveyor's benchmark on St Ann's Church

Whilst I was in the church an elderly man named Ronnie came over to talk to me about the bomb, he remembered in the 70s when Cannon Morgan was on loan to St Ann’s from the cathedral. Ronnie alluded to a playful rivalry between the cathedral and St Ann’s and he’d asked Cannon Morgan what he thought of the bomb landing but not detonating: “do you think it’s because we’re such good anglicans here at St Ann’s?” to which the cannon replied: "perhaps, or alternatively it’s because the devil knows his own".

St Ann’s was once again lucky to escape further bomb damage, during the 1996 IRA bomb the upstairs windows were blown in on both sides of the church. The quite lovely stained glass windows were not damaged.

When I set out to see the bomb today my roll of film became, quite coincidentally, something of a triptych of bomb scenes.

I left St Ann’s and decided to head over to Hilton House on Dale Street to see the film set for the upcoming BBC drama about the IRA bomb (From Here to There), it was only there for the afternoon and I wanted to speak to the locations manager so I thought I could get some photos whilst I was there.

I didn’t realise that the scene that was set up was the immediate aftermath of the bomb, and so found myself in a smokey street of exploded window displays, shattered glass, burning debris and fake fire officers. There was even a mock up of the famous post box that escaped the bomb unscathed.

Hilton House worked really well as the old Marks and Spencer (though some CGI work will be needed to recreate that famous curved canopy) and it was really haunting to watch as Bernard Hill and Philip Glenister walked by, in character, devastated.

A recreation of the post box that survived the bomb

And with two photos left on my roll I headed towards the developers, thinking I’d snap a gargoyle or some street art or anything along the way to use it up, then I remembered a place nearby that would be the perfect end to the roll.

Tib Street. I often walk by the shopfitter’s on Tib Street when their loading bay is open and I love to look down into it as it’s frozen in time as the air raid shelter it once was.

Today it was closed but the staff very kindly took me down there. Interestingly the emergency exit sign is above a boarded up hole in the wall deep in the centre of the cellar that must have led to either a tunnel under the street or into a neighbouring shelter as there can’t possibly be any other way out so far into the cavernous cellar.

It’s hard to see how large the space is and how many archways and separate rooms there are but it’s much bigger than the neighbouring cellars of Tib Street led me to believe (typically Tib Street cellars are tiny, oppressive spaces that were the original slums of industrious Manchester and where 16 families would live together in one room).

Here’s that sign, so remember to look out for it next time you walk by an open doorway in the Northern Quarter.