THE BURIED CRYPT

WRITTEN BY Hayley Flynn

READING TIME: 10 minutes

The extraordinary man who dug out the buried crypt beneath St Luke’s

The bombed out church, St Luke’s, stands at the top of Bold Street in Liverpool. The official name is St Luke’s in the City and was nicknamed the Doctor’s Church because of neighbouring Rodney Street which houses all the consultants and doctors in the area. St Luke is the patron saint of surgeons, physicians, and artists - fitting even more now that Ambrose Reynolds, original member of Urban Strawberry Lunch, is artist in residence at the church building and runs regular events in the venue including art installations and film screenings.

“We see ourselves as kind of guardians of this church; protecting it, stopping it from falling down, we try and make it a little bit better every day. We do out best with the garden. Even the rain water we’ve collected in the crypt that goes into here - every problem is turned into a solution. That’s very much the way we work.”

St Luke’s was bombed on 5th May during the 1941 May Blitz in Liverpool in an attempt to shut the port city down; shutting down the ports effectively shuts down the country. Ambrose tells me that churches were targeted to demoralise the residents. Twelve other churches were bombed; six were demolished, six were rebuilt and St Luke’s was abandoned and left as it was - a roofless cavern with grass in place of tiles and trees growing where supporting pillars would be.

The beams, burned to a cinder, can still be spotted in parts of the structure - blackened and torn apart. It was the burning beams that caused the roof to cave in, not the impact of a bomb itself, which is why so much of the rest of the church remains standing.

In the original bell tower, right above our heads, a beam juts out from one wall and has hung there, precariously, for seventy-two years. Ambrose, with an insouciant attitude to health and safety laughs and eventually suggests we stand somewhere else, just in case.

St Luke’s was famous for its bells, especially how they were framed - the first metal bell frame in the world. The bells were named Peace and Good Neighbour and they first rang out on 23rd April 1831 (shortly thereafter the neighbours lodged a complaint for disturbance of the peace).

Today, the bells are replaced by recovered alloy wheels (which you can hear chime at the end of the recording further down the article).

There are parts lying around in the bell tower that are largely unrecognisable, relics propped up against a crumbling wall.

AR: “These are original beams and bits that we’ve found. I think this is a part of a chair. That’s part, I think, of the original clock mechanism. The clock stopped at three thirty in the morning, which is when it was bombed. The bells came tumbling down and cracked and they were taken away to Manchester and stored until the 50s/60s and then they were sold as scrap. Makes you sick, doesn’t it.”

As we walk back into the centre of the building Ambrose points out the art displayed in the long grass and as we come along a pathway to a pond decorated with flowers and painted tyres he explains how it was made in the 1970s by a job creation project, a project that he himself was involved in; his first encounter with the building he became so fascinated with.

AR: “This was put in the 1970s…they did the pathwork as well and we think it was the consecration stone that was originally here. We didn’t know there was a pond there for ages and realised it rained a lot and left a soggy mess there, we got young offenders in and they cleaned it out and it was full of human waste, junky needles, dead rats and clothes. It’s our reservoir as well because there’s no water - when the church was bombed the water main was bombed at the same time, it burned for seven days and nights. So we have no water right now and we haven’t had water for seventy-two years.”

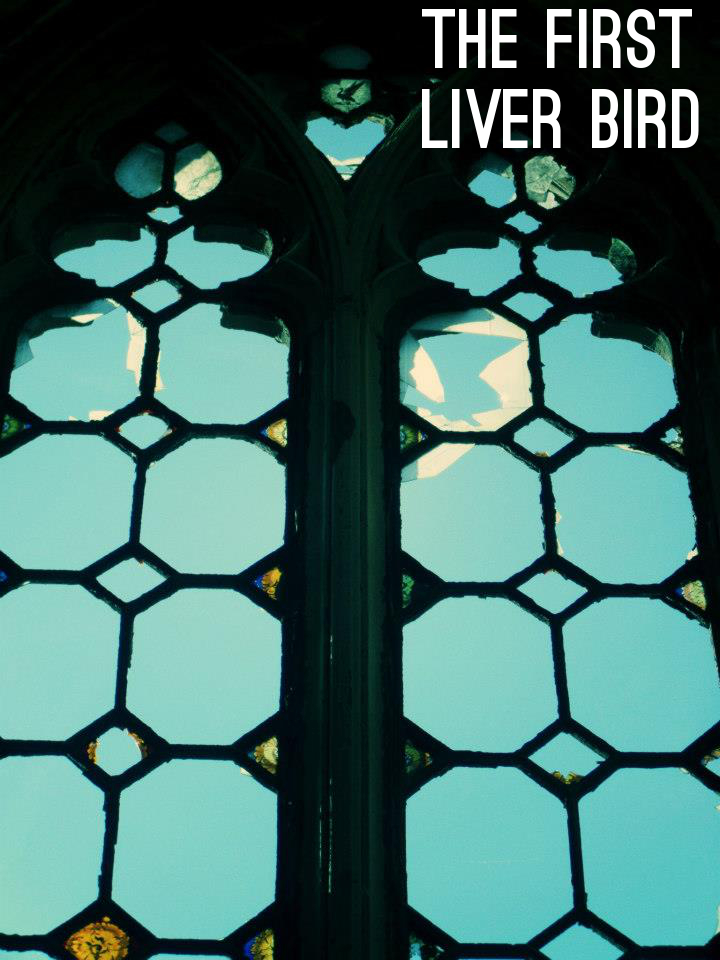

Scattered around the building are very minute elements which have defied the odds to survive - in the very corners of the windows two angels painted on the glass remain despite the bomb, the fire, and the onslaught of stones children have thrown at them.

AR: "These windows in the middle, some of these were still intact when I was a boy in the 60s and 70s and one of my earliest memories is these lads who were throwing rocks through them - my mum would box their ears. And that’s kind of when I got a bit obsessed with the building."

So the windows were intact even after the bomb?

AR: “There were actual figures intact in the middle. I know the elderly gentleman who was the one who put in the last set of windows in the cathedral in the 80s; he was ‘Mr Stained Glass’ and he came in and it took him about an hour to get from the door to here and he said ‘decommission these windows’ and he wrapped them up in brown paper and string and took them off to Manchester where all things Scouse end up. So those windows are still somewhere. On some Russian millionaire’s yacht by now but they still exist. But he missed those two angels.”

Exploring the structure is fascinating, as it Ambrose’s dedication and struggle to keep the light of life burning there but today I’m here with the sole intention of exploring underneath the church, in the newly uncovered crypt, and to meet the man who unearthed it…

An art installation in a corner of the church

AR: “We’re going to head into the really exciting part now, up until last year nobody had really been in the crypt apart from a few junkies. We picked up all the needles and we’ve made as safe as we can, we fumigated it as well, so it’s bug free. And we’re going to go under this room, under the steps and emerge in a room that’s the other side of that wall. We’ve got artefacts, Kevin’s done all the work, he’s been a real star. He’s done loads of the back breaking work. You need to wear a hardhat, and gloves because the poison is still active.”

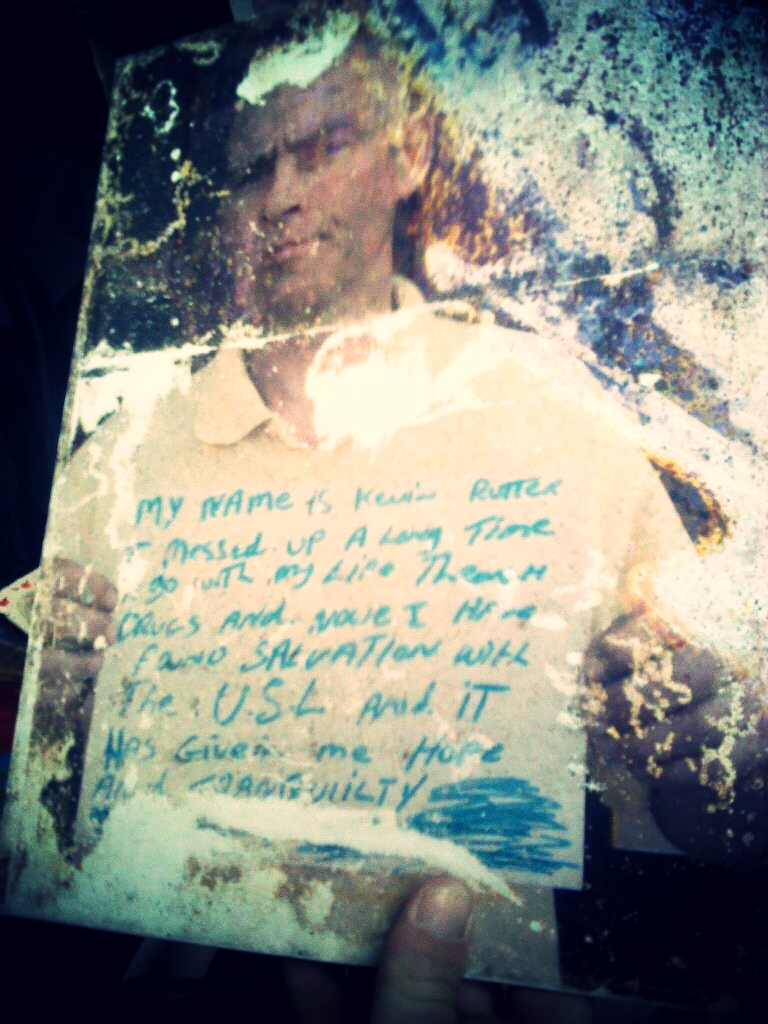

And so enters Kevin Rutter, a former addict who transferred his addictions from drink and drugs to ones of archaeology and architecture - he and the building are lifelines for each other. But I’m oblivious of this until we are deep in the crypt.

Kevin guides me around, he points out the bricked up second crypt where he suspects unofficial burials lie before moving on to indicate just what thirty-five tons of debris looks when piled up in a claustrophobic tunnel. The debris, the needles, the muck, it was all removed almost single-handedly by Kevin in eight days (a job the army were meant to be handling) and whilst inspecting an nineteenth century stove in an larger room I ask how he’s coped being in the damp and dark these last few weeks.

KR: "I was living in a cave that was fifty feet down and had a piece of rope going down, and the council came and put a big rock in front of it. There was a Russian community, a Polish community, Hungarian community…about three-hundred people living in the caves."

As if what he’s told me is the most normal thing in the world, which I guess to Kevin at some point it probably was, he changes tone and excitedly tells me to come and see the final part of the tour and leads me up an ancient stone staircase into a brightly lit room back on street level: “This is wonderland!”

In the room, one that hasn’t been accessed until the the crypt created a new path to it, stands a table of artefacts that have been uncovered in the dig. Mostly tiles, original roof slates, a few tools and a couple of well preserved shards of stained glass. Kevin picks up two of these glass pieces, one is a robotic looking fist, and holds them to the light and tells me:

"We call this The Hand of God. We're looking through a hundred years of glass into this century."

Kevin showing the height of the rubble

And in the background, behind the painted mechanical hand, is an empty window frame. Kevin puts the glass down and points back to the window, he asks me can I see it? He’s pointing at the tip of the frame and the evening light makes it clear that another piece of glass has remained intact in the church only this one is believed to be the first depiction of a Liver Bird in 1811, predating what was assumed to be the original at the Royal Liver Building by almost a century. The room we’re in hasn’t been opened in over seventy years so the find is something of a lost treasure.

The room is the original entrance, right under the bell tower, and now serves as a kind of living museum.

St Luke’s is Grade II listed, and apparently, the listing prevents Ambrose and his team installing suitable protection to make sure the Liver Bird doesn’t meet its demise at the hand of a wayward stone’s throw.

SO WHAT SPARKED THE CHANGE FOR KEVIN?

Back out on the street a dishevelled looking man spots us and shouts in recognition. Kevin waves then tells me: "That was me, eighteen months ago. A street drinker, and I just turned my life around. Something just went like that to me…I don’t know what happened…I shut my eyes, woke up and went…" and he holds his hands out, palm upwards as if he can’t explain what moved him to a new life of sobriety.

"I was just walking past one day, seen the church and walked in. Spoke to Ambrose, shook his hand and said ‘any chance of doing a bit of gardening?’ he said ‘yeah’, I said ‘how about doing some painting?’ he said yeah…I lived on the street smoking drugs; I got off the drugs. Drinking beer; I got off the beer. I’ll still go out for a pint with my mates at the weekend now and again but I managed to get back into life, I’m in a hostel, I just do it [the voluntary work] for something to do. Now, I’m addicted to the church. I’m addicted to the church. I love it."

And the most enlightening part of that is how this isn’t a man discussing religion, it’s a man who has replaced a destructive habit with bricks and stained glass that was once a church. It’s the playground of artists and musicians who offer a sense of purpose, and a helping hand to anyone who wants to bring their own story to the site. For Kevin this is a hobby that he dedicates his life to, and his passion is such that he was able to visit France to learn more about heritage and restoration on an archaeology site.

In the reception of the building Kevin digs out photographs of the other homeless people who have turned to Ambrose and Urban Strawberry Lunch for help through the years. He reels off names of friends he’s watched try and fail and ultimately die long before they should. Although obviously saddened by the realisation of how many people he’s lost he shrugs it off "It’s just one of them things. Move on".

Kevin’s photograph from when he first came to volunteer with Urban Strawberry Lunch at St Luke's. It reads:

“My name is Kevin Rutter, I messed up a long time ago with my life, the drugs, and now I have found salvation with the USL and it has given me hope and tranquility.”

At the time of interview Ambrose, and Urban Strawberry Lunch, were not receiving funding for their efforts instead they rely upon public donations. Kevin was living in a hostel and volunteering all his time to St Luke’s.

The building is open Thursday-Sunday, 12-6pm throughout the year (apart from January).

All images by Hayley Flynn, Skyliner.